The Unique Vision of an Artist: Seeing the World Differently

(or: Why Some People See Cracked Sidewalks and Others See Avant-Garde Paving Projects)

Artists have a unique way of perceiving the world, capturing the subtle nuances that often go unnoticed by others.

It’s not that they have superpowers—although it kind of feels that way when you’re around them—but that they’re operating on a different perceptual frequency where the mundane gets hacked into something meaningful or beautiful or just weirdly poetic.

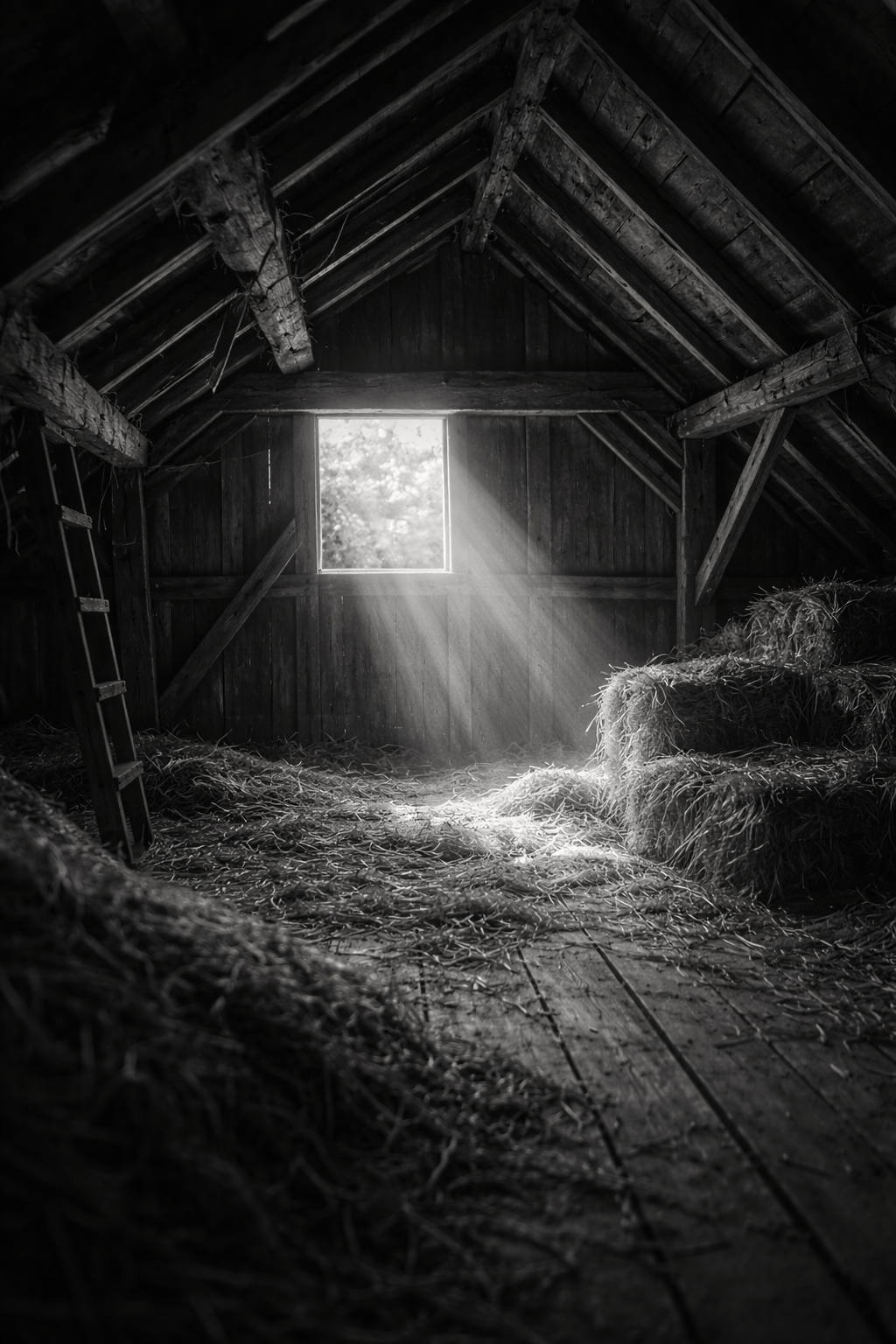

Seeing Colors and Light Like No One Else (or: Why Monet Was Basically Obsessed with Hay)

One of the most brain-twisting aspects of the artist’s vision is how they perceive light and color. This is one of those concepts that seems obvious until you really start to think about it. Like, you and I look at the sky, and we’re like, “Blue. Sometimes gray. Occasionally a sort of apocalyptic orange.”

An artist? They notice things like the way dawn seeps in around the edges of night, or how dusk looks different if you’re in a city versus a field.

Consider Claude Monet, a guy who essentially spent his entire artistic career having a polite but determined argument with the concept of light. The haystacks? Not just haystacks. They were more like elaborate props in a one-man theatrical performance called Light Does Weird Stuff to Stationary Objects.

Monet’s obsessive repetition—the same haystack painted at dawn, at sunset, in snow, in fog—is essentially him saying, “Do you see how reality is never actually the same twice? Are you paying attention?”

Finding Beauty in the Everyday (or: How to Fall in Love with Rust)

The other mind-warping thing is how artists see beauty in stuff that most of us classify as irrelevant or even ugly. Imagine looking at a rusted fence and instead of thinking “eyesore,” you think “textural masterpiece.” The problem (for most of us) is that our brains are running on some outdated cultural software that equates beauty with symmetry, cleanliness, or general Instagram readiness.

Take Georgia O’Keeffe. She basically decided that flowers were insufficiently noticed, so she zoomed in until the petals looked like alien landscapes. It’s not just about seeing beauty—it’s about refusing to let your brain skim over the familiar. She’s basically telling us, “Stop acting like flowers are just pretty background noise. These things are intense. They’re practically operatic.”

Emotions Painted into Reality (or: Why Van Gogh Wasn’t Exactly Going for Photorealism)

Here’s another thing: artists don’t just see things—they feel them, and that’s crucial. There’s this weird cultural assumption that emotions are these squishy, peripheral phenomena that interfere with clear thinking, but artists weaponize emotion to make their perception more acute.

Van Gogh’s Starry Night isn’t just a pastoral nightscape with swirly bits. It’s basically an externalized version of what happens when your brain decides to merge joy and despair into one single, overwhelming sensation. The stars are literally pulsating because Van Gogh’s brain is pulsating.

If you or I tried to paint that sky, it would probably look like a Windows desktop background with some shiny dots. But Van Gogh turned it into this frenetic, vibrating thing because that’s how it felt to him. It’s like reality filtered through a mind that doesn’t just see but also processes through this high-octane lens of emotional turbulence.

Conclusion: Seeing Like an Artist (or: How to Stop Being Bored by Sidewalks)

So, what can we non-artists take from all this? Maybe it’s just the awareness that most of us are seeing on autopilot. Maybe the real trick isn’t to train ourselves to be artistic per se, but to break out of the habit of superficial observation. Next time you’re out, maybe try to notice how the rain darkens pavement in irregular patches or how sunlight turns dust motes into floating constellations.

It’s not about convincing yourself that everything is beautiful or profound—because honestly, some things are just boring. But it’s about not defaulting to boredom as your primary mode of perception. The artist’s gift isn’t just in creating—it’s in seeing. And maybe if we paid just a little more attention, we’d start to see the cracks not as flaws but as interesting, fractal stories etched into the concrete.

Leave a comment